Teaching the Oppressed How to Fight Oppression

By Ramzy Baroud

An American activist once gave me a book she wrote detailing her experiences in Palestine. The largely visual volume documented her journey of the occupied West Bank, rife with barbered wires, checkpoints, soldiers and tanks. It also highlighted how Palestinians resisted the occupation peacefully, in contrast to the prevalent media depictions linking Palestinian resistance to violence.

More recently, I received a book glorifying non-violent resistance, and which referred to self-proclaimed Palestinian fighters who renounced violence as “converts”. The book elaborated on several wondrous examples of how these “conversions” came about. Apparently a key factor was the discovery that not all Israelis supported the military occupation. The fighters realized that an environment that allowed both Israelis and Palestinians to work together would be best for Palestinians seeking other, more effective means of liberation.

An American priest also explained to me how non-violent resistance is happening on an impressive scale. He showed me brochures he had obtained during a visit to a Bethlehem organization which teaches youth the perils of violence and the wisdom of non-violence. The organization and its founders run seminars and workshops and invite speakers from Europe and the United States to share their knowledge on the subject with the (mostly refugee) students.

Every so often, an article, video or book surfaces with a similar message: Palestinians are being taught non-violence; Palestinians are responding positively to the teachings of non-violence.

As for progressive and Leftist media and audiences, stories praising non-violence are electrifying, for they ignite a sense of hope that a less violent way is possible, that the teachings of Gandhi are not only relevant to India, in a specific time and space, but throughout the world, anytime.

These depictions repeatedly invite the question: where is the Palestinian Gandhi? Then, they invite the answer: a Palestinian Gandhi already exists, in numerous West Bank villages bordering the Israeli Apartheid Wall, which peacefully confront carnivorous Israeli bulldozers as they eat up Palestinian land.

In a statement marking a recent visit announcement by the group of Elders to the Middle East, India’s Ela Bhatt, a ‘Gandhian advocate of non-violence’, explained her role in The Elders’ latest mission: “I will be pleased to return to the Middle East to show the Elders’ support for all those engaged in creative, non-violent resistance to the occupation – both Israelis and Palestinians.”

For some, the emphasis on non-violent resistance is a successful media strategy. You will certainly far more likely to get Charlie Rose’s attention by discussing how Palestinians and Israelis organize joint sit-ins than by talking about the armed resistance of some militant groups ferociously fighting the Israeli army.

For others, ideological and spiritual convictions are the driving forces behind their involvement in the non-violence campaign, which is reportedly raging in the West Bank. These realizations seem to be largely lead by Western advocates.

On the Palestinian side, the non-violent brand is also useful. It has provided an outlet for many who were engaged in armed resistance, especially during the Second Palestinian Intifada. Some fighters, affiliated with the Fatah movement, for example, have become involved in art and theater, after hauling automatic rifles and topping Israel’s most wanted list for years.

Politically, the term is used by the West Bank government as a platform that would allow for the continued use of the word moqawama, Arabic for resistance, but without committing to a costly armed struggle, which would certainly not go down well if adopted by the non-elected government deemed ‘moderate’ by both Israel and the United States.

Whether in subtle or overt ways, armed resistance in Palestine is always condemned. Mahmoud Abbas’ Fatah government repeatedly referred to it as ‘futile’. Some insist it is a counterproductive strategy. Others find it morally indefensible.

The problem with the non-violence bandwagon is that it is grossly misrepresentative of the reality on the ground. It also takes the focus away from the violence imparted by the Israeli occupation – in its routine and lethal use in the West Bank, and the untold savagery in Gaza – and places it solely on the shoulders of the Palestinians.

As for the gross misrepresentation of reality, Palestinians have used mass non-violent resistance for generations – as early as the long strike of 1936. Non-violent resistance has been and continues to be the bread and butter of Palestinian moqawama, from the time of British colonialism to the Israeli occupation. At the same time, some Palestinians fought violently as well, compelled by a great sense of urgency and the extreme violence applied against them by their oppressors. It is similar to the way many Indians fought violently, even during the time that Mahatma Gandhi’s ideas were in full bloom.

Those who reduce and simplify India’s history of anti-colonial struggle are doing the same to Palestinians.

Misreading history often leads to an erroneous assessment of the present, and thus a flawed prescription for the future. For some, Palestinians cannot possibly get it right, whether they respond to oppression non-violently, violently, with political defiance or with utter submissiveness. The onus will always be on them to come up with solution, and do so creatively and in ways that suit our Western sensibilities and our often selective interpretations of Gandhi’s teachings.

Violence and non-violence are mostly collective decisions that are shaped and driven by specific political and socio-economic conditions and contexts. Unfortunately, the violence of the occupier has a tremendous role in creating and manipulating these conditions. It is unsurprising that the Second Palestinian Uprising was much more violent than the first, and that violent resistance in Palestine gained a huge boost after the victory scored by the Lebanese resistance in 2000, and again in 2006.

These factors must be contemplated seriously and with humility, and their complexity should be taken into account before any judgments are made. No oppressed nation should be faced with the demands that Palestinians constantly face. There may well be a thousand Palestinian Gandhis. There may be none. Frankly, it shouldn’t matter. Only the unique experience of the Palestinian people and their genuine struggle for freedom could yield what Palestinians as a collective deem appropriate for their own. This is what happened with the people of India, France, Algeria and South Africa, and many others nations that sought and eventually attained their freedom.

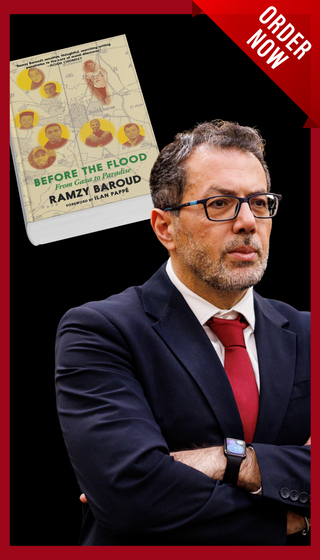

– Ramzy Baroud (www.ramzybaroud.net) is an internationally-syndicated columnist and the editor of PalestineChronicle.com. His latest book is My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story (Pluto Press, London), now available on Amazon.com.

0 Comments