Revolutionary Egypt Forges Ahead

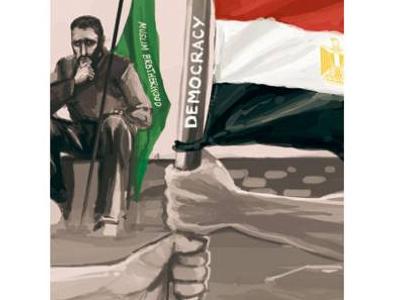

(Image Credit: Niño Jose Heredia/Gulf News)

By Ramzy Baroud, Special to Gulf News

The streets of Cairo are chaotic. Each driver seems to be governed by an entirely different set of traffic rules. Yet, somehow, the cars continue to move forward — for the time being, at least.

Egypt is finally free, and Egyptians are savouring every moment of their newly found freedom. Thanks to a popular revolution, itself a model of people’s power, former president Hosni Mubarak is now in jail. His most recent appeal — seeking forgiveness from his people — was as much a failure as his past attempts at wooing a rebelling nation.

Egyptians now speak of national priorities, desperately trying to unite their agendas to face the challenges ahead.

"Do you call this a street?" a friend said, as we arrived in what was apparently one of Cairo’s fanciest neighbourhoods. Rubbish was strewn everywhere. Garbage collectors, like other city workers, have been striking intermittently, leaving parts of the city almost completely neglected.

The situation was much worse during the revolution. When the former ruling regime grew desperate before the millions of protesters in Tahrir Square, they orchestrated chaos, releasing thousands of criminals into the streets to wreak havoc. "It was one of the scariest times of my life," Na’ima, a middle-aged mother of three, says. "I knew that a thug could break the door down at any moment and do as he pleased."

There was no one to call for help, as the National Democratic Party (NDP) hastily removed the police from the streets. Desperate Egyptians were left to fend for themselves.

Na’ima’s son was one of those who joined the popular committees which did their best to guard the streets of Egyptian cities. The spontaneous organisation that defined the early days of Egypt’s revolution is truly awe-inspiring, especially as Egyptian society has long been denied the basic structure of civil society, and was forced to swap the principles of citizenship with political tribalism — solely based on party affiliation, favouritism and corruption.

Now, it is a time for rebuilding, restructuring and redefining. The task at hand is arduous. Starting January 25, and for 18 days straight, ordinary Egyptians defined what it actually meant to be Egyptian. They articulated their demands without attachment to a specific political agenda, presenting a unified image of a country resurrecting itself after many years of repression. Although some political parties tried to capitalise on the popular revolution for short-term objectives, the entire opposition soon merged into the multitudes of ordinary Egyptians from all walks of life. A new Egypt was indeed being born.

However, the unity of four months ago is facing massive challenges. Now that the people are back in their homes, politics reign supreme. The Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt’s largest and oldest Islamic organisation, is certainly one of the new political forces that will define the new Egypt. Not everyone here is pleased by that prospect.

"In Tahrir Square today, over a million chanted against the Brotherhood and Supreme Council of the Armed Forces" [SCAF]," Syed, a driver, said after a recent protest, as he negotiated his way through the streets of the Masr Al Jididah neighbourhood.

"Is that a good or a bad thing?" I asked.

"Who knows. The future of Egypt is now in the hands of God."

Curiously, many Egyptians make a distinction between SCAF and the military. Others accuse the Brotherhood of political manipulation, and of striking backroom deals with the military leadership. Liberal media and commentators cite all sorts of ‘historical proofs’ to demonstrate the compromising nature of the Brotherhood. This could extend as far back as 1954, or as recently as the group’s agreement to meet former vice-president, Omar Sulaiman.

The ‘Second Day of Rage’ — Friday, May 27 — was meant to convey to both the army and the Brotherhood that Egyptians were ready to challenge any attempts to undercut their revolutionary achievement. These protests in Tahrir Square ended without violence. While the day was later portrayed as an example of the disunity that could mar the Egyptian revolution, I tried to stay positive.

After over 80 years in politics, fighting colonialism and oppression, the Brotherhood managed to survive against tremendous odds. Facing near constant attack, including mass arrests and torture, the Brotherhood learned politics the hard way. The group has survived through many means, including political alliances, but never under its own name. It took political savvy and experience to survive this long, and to influence Islamic political movements the world over.

Revolutionary Egypt, however, is in no mood for the old-style politics. Many here speak of unity, citizenship, equality and democracy. Despite the Brotherhood’s repeated assurances of not seeking political domination or Sharia-based government, many in Tahrir Square have serious doubts.

Yet, despite everything, the Cairo traffic stubbornly continues to move forward.

On the outskirts of Cairo, army tanks are everywhere. Egyptians don’t perceive the army as an enemy — the message of unity between the people and the army continues to resonate in Tahrir Square. And even with growing doubts, Egyptian society is boldly coming out of its forced hibernation, articulating its rights and expectations like never before.

– Ramzy Baroud is an internationally-syndicated columnist and the editor of PalestineChronicle.com. His latest book is My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story.

0 Comments