On Spirituality and Low-Quality Entertainment: Ramadan Accentuates Inequality in the Arab World

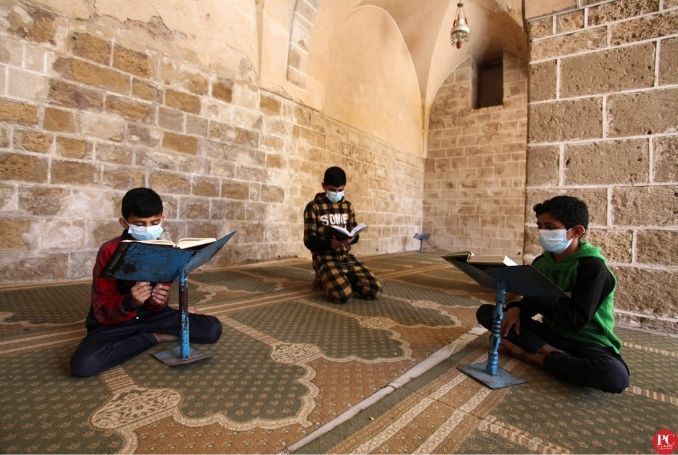

Palestinian Muslims performing prayers and reading Quran in the Great Al-Omari Mosque in the early days of the holy month of Ramadan. (Photo: Fawzi Mahmoud, The Palestine Chronicle)

By Ramzy Baroud

Ramadan, the holy month of fasting in Islam, should be a time of spiritual reflection and a reordering of the Ummah’s collective priorities. Unfortunately, in the age of globalization, unmitigated consumption and self-centered, individualistic approach to life, our relationship with Ramadan is veering off from its intended goal to something else entirely.

Ramadan is usually the most charitable month for Muslims, a time that is dedicated to prayer, to giving, to seeking forgiveness. It is an amalgamation between the individual’s spiritual rebirth on the one hand, and the strengthening of the Ummah, the Muslim nation, on the other.

It is during this month that it feels as if political boundaries are removed and Muslims claim a new sense of collective identity, regardless of where they are in the world. Their point of unity becomes their mutual fast and the associated communal activities – feeding the hungry, clothing the poor, caring for the orphans, and so on.

It is quite misleading to understand Ramadan as a time in which Muslims refrain from eating or drinking from sunrise to sunset. Yes, that too, but Muslims are also required to refrain from much more – committing bad deeds, speaking disparagingly of others, lying, cheating or even harboring animosity towards one another.

But is this truly transpiring in Arab and Muslim countries at the moment? With the globalized media making Arab audiences, for example, a single media market, Ramadan is now affiliated with a lucrative entertainment industry, measured by billions of dollars every year. From Ramadan TV series, to talk shows and concerts and much more, Ramadan is now the most financially rewarding month for the Arab media industry. Rarely does the essence of Ramadan itself register as a central theme in any of this frivolous entertainment.

According to a recent Carnegie Corporation study, “about 250 million people out of 400 million across 10 Arab countries, or two-thirds of the total population, were classified as poor or vulnerable”. The report refers to this as “mass pauperization”, indicating that a poor Middle Eastern family in the present time is likely to remain poor for several generations to come.

The Middle East remains one of the most unequal regions in the world. In fact, according to Carnegie, it is already the most unequal, as governments are either unable or unwilling to provide basic services to their own populations.

Young people, including university graduates, have little job opportunities, with no hope looming on the horizon, leaving them with limited options. For many of these youth, migration becomes the best-case scenario. It is in these communities that radicalism often presents itself as the answer to life’s despair.

From food insecurity to gender inequality, to rampant illiteracy, the Arab world is rife with problems. Unlike other regions in the developing world, many Arab countries do not really seem to be developing at all. One of the reasons behind the stagnation, if not the outright collapse, is the fact that the Middle East is in the throes of seemingly never-ending wars. In truth, no matter the outcome of any of these wars, neither democracy nor socio-economic reforms, or equality or human rights are likely to be delivered.

During Ramadan, one is compelled to reflect on all of this. Yes, we are meant to kneel down in prayer and to raise our open palms to Heaven, beseeching God for mercy and forgiveness. But we are also meant to look and reflect upon our own affairs, our own nations that are crumbling, imploding or losing their sense of collective mission entirely.

In Islamic history, stories are often told of how the Ummah felt the pain of an oppressed individual no matter how far she or he was from the center of power.

“The parable of the believers in their affection, mercy, and compassion for each other is that of a body. When any limb aches, the whole body reacts with sleeplessness and fever,” says one of the many hadiths, sayings of Prophet Mohammed that illustrate the notion of solidarity in Islam.

Where are we from that elevated notion of love and concern for one another? Muslims everywhere are aching, in the Middle East, in Asia, and as far as China, France and the Central African Republic. This reality manifests itself in the flood of refugees pouring out of Muslim countries and regions towards every possible direction. Not only one limb is aching in this Muslim body, but the whole Ummah is in anguish.

Therefore, one is baffled as precious opportunities are wasted. Instead of using Ramadan as a platform to reset the Ummah’s energies so that they may spring forward with a determined strategy to deal with the many compelling problems, Ramadan becomes an opportunity for useless, low-quality entertainment that is designed to distract the people from their urgent challenges.

Ramadan is not a time for eating, but fasting; it is not a time for singing and dancing, but reflecting and praying; it is not a time for the accumulation of wealth, but for generosity and charity. More, Ramadan is the time where the Ummah should, once more, rediscover its identity and collective strength, for the sake of all Muslims; in fact, for the sake of humanity at large. Ramadan Mubarak.

– Ramzy Baroud is a journalist and the Editor of The Palestine Chronicle. He is the author of five books. His latest is “These Chains Will Be Broken: Palestinian Stories of Struggle and Defiance in Israeli Prisons” (Clarity Press). Dr. Baroud is a Non-resident Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Islam and Global Affairs (CIGA) and also at the Afro-Middle East Center (AMEC). His website is www.ramzybaroud.net

0 Comments