Nakhwa without Borders: Gaza and the End of ‘Arab Gallantry’

It was al-Karama (dignity) that forced Gaza to the streets in the First Palestinian Uprising.

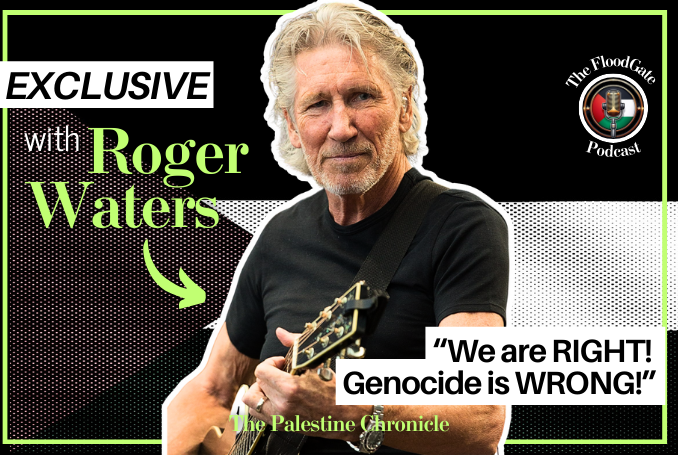

By Ramzy Baroud

On its own the Arabic word al-Nakhwa, means “gallantry.” Combined with the word “al-Arabiya” – “Arab gallantry” – the term becomes loaded with meanings, cultural and even political implications and subtext. But what is one to make of “Arab gallantry” during and after Israel’s most brutal war on Gaza between 8 July and 26 August which killed 2,163 Palestinians and wounded over 11,000 more?

Is this the end of Arab Nakhwa? Did it even ever exist?

As a Palestinian Gaza refugee from a simple peasantry background, I was raised to believe that al-Nakhwa was an essential component of one’s Arab identity. Together with al-Rojoula – “manhood/fortitude/heroism” – al-Karm – “generosity” – al-Karama – “dignity” – and al-Sharaf – “honour” – were all indispensable tenants in the character of any upright person. The alternative is unthinkably shameful.

Thus, it is no wonder that Palestinian national songs, and the slogans for successive rebellious generations in Palestine have borrowed heavily from such terminology. It was al-Nakhwa that compelled Gaza to rise in solidarity with the victims of al-Aqsa Mosque clashes in 2000, which ushered in the painful years of the Second Palestinian Uprising (2000-2005). It was al-Karama (dignity) that forced Gaza to the streets to protest the killing of four Palestinian cheap labourers by an Israeli truck driver, leading to the First Palestinian Uprising (1987-1993). It was al-Sharaf (honour) that made Gazans fight like warriors of ancient legends to prevent Israeli troops from taking over the impoverished and besieged Gaza Strip in the most recent war.

But the lack of reactions on Arab streets, – Perhaps Arab societies are too consumed fighting for their own honour and dignity? – and the near complete silence by many Arab governments as Israel savaged Gaza civilians, forces one to question present Arab gallantry altogether.

Yet millions protested for Gaza across the world in a collective global action unprecedented since the US war in Iraq in 2003. South American countries led the way, with some governments turning words into unparalleled action, not fearing western media slander or US government reprisals. Few Arab countries even came close to what the majority Christian Latin American countries like Ecuador have done to show solidarity with Gaza.

And when a ceasefire was declared on 26 August, it became impossible for Israeli or even western media to argue in earnest that Israel had won “Operation Protective Edge.” They tried, but the closest they managed to argue was that there were no winners. Others acknowledged that Gaza had won the war by defeating every war objective laid out by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Hardly shocking, although certainly dishonourable, some Arab journalists who stayed largely quiet as the Palestinian death toll in Gaza grew rapidly, went on a well-organised crusade. While they shed crocodile tears for Gaza’s children, they insisted that Gaza lost, strengthening Netanyahu’s desperate narrative that his war had achieved its objectives. The Gaza-didn’t-win line was repeated by many well-paid journalists and commentators as to defeat the prevailing notion that resistance was not futile. For them, it seems that Palestinians need to accept their role in the ongoing Arab drama of being perpetual victims, and nothing more. A strong Palestinian, practically and conceptually, is the antithesis to the dominant line of the current Arab political script that is predicated on strong rulers and weak nations. Since the Palestinian Nakba (Catastrophe), the Palestinian is only idealised as a hero in poetry and official text, but an eternal casualty in everyday life.

Some of these pseudo-intellectuals didn’t even muster enough Nakhwa to extol Gaza on its resistance and the sheer enormity of its sacrifices. Most of Gaza’s resistance fighters (who mostly come from Gaza’s poor refugee classes) reportedly fasted (no food or water from dawn to dusk) as they fought throughout the month of Ramadan. Many would break the fast on few dates, if any. Compare this to the endless supplies of food, and everything else that remained available in abundance to invading Israeli troops. Even if these commentators sincerely rejected the “Gaza victory” narrative, wasn’t the sheer fortitude of these men and women deserving of a mere acknowledgement of a few words written by the well-fed “intellectuals” operating from faraway hotel lobbies in rich Arab capitals?

Since the introduction of pan-Arab satellite television news networks, the term “Arab gallantry” was brought into question endless times. In fact, “Iyna al-Nakhwa al-Arabiay?” – where is the Arab gallantry?’ – was perhaps the most oft-repeated question raised by ordinary Arab callers taking part in television political debates. The question was uttered mostly in the Palestinian context, but, in the last decade also in the cases of Iraq and Syria.

There is no definite answer as of yet, but it is not that Arab gallantry is in abundance within ruling Palestinian classes either.

Just days following the ceasefire, the leaders of the Ramallah political class unleashed verbal attacks against the former Hamas government over money, salary and phony coup attempts. For Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, per the leaked protocol of his meeting with Hamas’ Khaled Meshaal in Doha, the war in Gaza seemed a secondary matter, as the 80-year-old was overwhelmed by some paranoia that everyone was conspiring against him. His Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah, who behaved as if his “premiership” didn’t include Gaza during the war, returned to action as soon as the ceasefire announcement was made. His government didn’t feel any particular urgency to pay salaries of Gaza employees who were hired by the previous Gaza government.

As if things couldn’t get any worse, a leaked letter provided to French lawyers by the deputy prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) showed that Abbas’ government actually blocked a Palestinian application to the ICC that is aimed at trying Israeli government and military leaders for alleged war crimes. Here the discussion over gallantry, dignity and honour ends, and a whole different set of terminology begins.

The shameful factionalism has reached a point where Fatah officials are accusing the former Gaza government for being responsible for the loss of lives among Gaza refugees as they make desperate attempts to escape the strip towards Europe atop crowded boats. Agenda-driven Arab commentators are joining in, some blaming both sides equally, as if those who resisted are equal to those who conspired.

Embattled Netanyahu is getting a badly needed break as Palestinian officials in Ramallah and some Arab media commentators are circuitously blaming Gaza for Israel’s own wars and war crimes. While Palestinians continue to gaze at the rubble of their destroyed lives in Gaza, they receive little support and solidarity from their Arab neighbours, or from their won “brethren” in Ramallah.

When Arab media commentators laud Netanyahu for killing Palestinians in Gaza and a UN spokesman weeps on the air, crying for Gaza’s victims, one is forced to question old beliefs about one’s own supposed exceptionalism. It has turned out that Nakhwa has no borders, and can extend from Bolivia to Sir Lanka, and from South Africa to Norway.

– Ramzy Baroud is a PhD scholar in People’s History at the University of Exeter. He is the Managing Editor of Middle East Eye. Baroud is an internationally-syndicated columnist, a media consultant, an author and the founder of PalestineChronicle.com. His latest book is My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story (Pluto Press, London).

0 Comments