Convenient Racism: The ‘Us’, ‘Them’ and ‘Non’ Factors

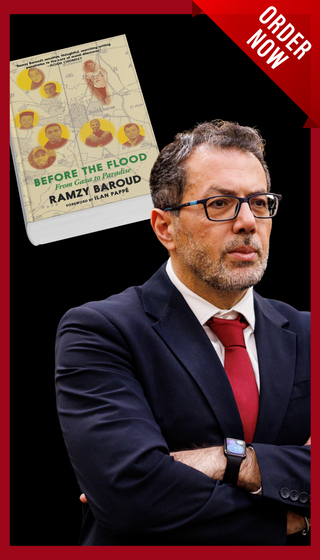

By RAMZY BAROUD

Racism is, among many things, convenient. It provides simplified, definite and ready-to-serve answers to complex and compounded questions. Racists, in turn, come from all walks of life; their motivation and the root causes behind their contemptible views of others may differ, but the outcome of these views is predictably the same — racial discrimination, social and political oppression, religious persecution and war.

The textual definition of racism pertains only to race, but in practice racism is a consequence of groupthink, whereby a group of people decides to designate itself as a collective and starts delineating its relationship with other collectives — or other people in general — with a sense of supremacy. When coupled with economic and/or political dominance, supremacy translates into various forms of subjugation and cruelty.

The adulation of the self/collective and the disparagement of the other is an ancient practice, as old as human civilisation itself. It is everlasting for the simple reason that it has always served as a political and economic tool and will likely remain effective so long as the quest for political and material power drives our behaviour.

It is also pertinent to stress that the need for this negative group designation is not always as straightforward as ‘black’ and ‘white’. For example, less economically advantaged Eastern Europeans seeking (competing for) employment in Western Europe find themselves lumped in the same group and subject to all sorts of classifications. Equally convenient has been the caricatured misrepresentation of ‘Arabs’ by mainstream media, which serves to further specific political and economic interests.

Ironically, an extreme form of racism also exists in some Arab countries, where foreign workers find themselves placed in a hierarchy based on country of origin. Western European and Americans top the scale and are readily accommodated, while South-East Asians are often at the bottom. A very qualified Asian engineer, for example, may find himself getting paid a lot less than a French one with relatively little experience.

In some countries, like South Africa, racism has wrecked havoc on society for generations. It manifests itself in the refusal of some people to identify with their original ancestral cultures, because they fear that such affinity would negate the fact that they are ‘full’ South African citizens (a right for which they fought a most arduous fight).

In Malaysia, which exhibits considerable social harmony when compared to some of it neighbours, racial classification is still very much real. Despite the government’s commendable efforts to accentuate the Malaysian national model while carefully underscoring the Malay, Chinese or Indian sub-groupings, members of these groups are wary of their statistical representation in Malaysian society. Some react by stressing their number in comparison to the other groups, while others tirelessly underscore the types of discrimination they experience at the hands of those with the political and economic advantages.

While racism is universally recognised, few individuals would admit to their own prejudices and racist tendencies. Moreover, it would be self-deceiving to view racism as a purely western phenomenon. While the western model of racism, influenced by 18th century colonialism, is unique in many respects, group prejudices based on class, race and religion are shared almost equally between all nations.

The racism of those with political, military and economic power is often violent and detrimental, but it is important to remember that the underdog can be just as racist. An Arab reader from London sent me an email demanding that I explain myself for collaborating on various projects with some well-known Jewish authors. ‘You are either naïve or you are selling out,’ she wrote. It made no difference to her that these authors are anti-Zionist and have been, for many years, on the frontline of the struggle for Palestinian rights and justice. She simply couldn’t break away from a deeply ingrained racist belief that ‘Jews are not to be trusted.’

Of course, this is not an Arab, but a global predisposition; prolonged conflicts and wars tend to validate and inflate already existing prejudices. Although the Israeli educational system has produced generations of students saturated with grossly misleading images of Arabs and Palestinians, the relationship between Arabs and Jews hasn’t always been negative. For centuries, both groups lived in harmony; some of the best Arab poets of past times were Jews and some of the most luminous Jewish texts were written originally in Arabic. Unfortunately conflict and war have a way of undermining such facts; racism in Israel is so intense now that few dare use the term ‘Arab Jew’.

Even when it doesn’t pertain to races, most people seem to slide easily into greater tribal memberships that divide the world into ‘us’ and ‘them’, often using words of negation and often utilising religion. The ‘non’ factor becomes very useful here — ‘non-Muslim’, ‘non-Jew’, ‘non-Christian’, and so on. Such negations are never well-intended and always produce negative results. Less apprehensive terms such as ‘non-democratic’ (a neo-colonial equivalent to ‘un-civilized’ perhaps?) could be similarly loaded and dangerous and are often used to promote and justify war.

It remains to be said that a true fight against racism and various other types of group prejudice requires first accepting personal responsibility in shaping one’s own society, and this includes the racism that exists within it. Martin Luther King, Jr refused ‘to accept the view that mankind is so tragically bound to the starless midnight of racism and war that the bright daybreak of peace and brotherhood can never become a reality.’ We, too, must uncompromisingly reject such a view if we truly wish for peace, harmony and equality to replace war, social discord and injustice.

-Ramzy Baroud is a Palestinian-American author and editor of PalestineChronicle.com. His latest book is The Second Palestinian Intifada: A Chronicle of a People’s Struggle (Pluto Press, London). His articles are archived at ramzybaroud.net.

0 Comments