Gaza’s Kite Runners

By RAMZY BAROUD

When seen from a distance, kites in Gaza may look quite ordinary. But while Gazan children, in many respects, are just children, their kites are hardly ordinary. Often adorned by the red, black, green and white of the Palestinian flag, Gazan children’s kites are expressions of defiance, hope and the longing for freedom.

This is hardly a cliché. People living under oppressive rules take every opportunity to express defiance, even through such symbolic ways.

Born and raised in Nuseirat Refugee Camp in the Gaza Strip, I remember my first kite. It, like most kites, carried the colors of the flag. The kite was the work of my older brother, now a successful medic in the West Bank. He obliged before my incessant cries for a kite despite my father’s objections. But why should a father object to something so seemingly harmless? Simple.

A notorious Israeli military camp and detention center was stationed on the outskirts of our refugee camp, between Nuseirat and Buraij. The military camp served multiple purposes. It was to immediately dispatch troops into our refugee camp at the first sign of protest. Further, the men stationed there guarded a nearby Jewish settlement. Finally, it also served as a temporarily prison where Palestinian activists suffered torture before being hauled off to Gaza’s central prison, or worse, Al-Nakab.

The military camp however, hardly enjoyed a moment of peace. Students and other refugees from adjacent refugee camps would descend into the Israeli military grounds, almost daily with marches; carrying flags, throwing stones and demanding that the soldiers’ depart. Of course, the soldiers didn’t oblige, and my refugee camp paid a heavy price in blood with every confrontation.

In the summer, in Gaza’s scorching heat and humidity, we had two escapes, swimming in the sea and flying kites. The first option was interminably blocked by the Israeli military under various guises. During the Intifada of 1987-93, the sea fell under Israeli siege. My house was very short walk from the beach, yet somehow, we spent over seven years without visiting it once. Not once. And so kite running became the most favored pastime.

Gaza’s children don’t buy ready-made-kites. There was no such thing. They construct them by hand and with unparalleled craftsmanship. To be entirely honest, I was terrible at making kites, as I am at anything that requires manual skills. The kite maker in the family was my older brother Anwar. His skill was both impressive and troubling. The source of trouble lied in the fact that children made kites carrying the colors of the flags and other symbols of resistance at the time, such as the initials: P.L.O. They often flew them to be visible from the Israeli military camp, and if the wind was right, right on top of it. The cleverest amongst the kite runners were those who managed to drop the kite, in an unprecedented moment of sacrifice, to fall right into the military camp.

During the Uprising’s summers, there would be dozens of kites, all red, black, green and white wavering atop the Israeli military camp and temporary detention center. The soldiers would often fly into a rage, storm the camp, seeking their target: children with kites. We could determine the location of the raid when all the kites from a particular location would fall from the sky in unison.

One afternoon, I sat upon the staircase of our home in the camp, a white cinderblock home, adorned with patriotic graffiti. It was safe to fly my kite as my father was in Israel, joining tens of thousands of Palestinians who negotiated a living wage under the harshest of circumstances. Out of nowhere, Israeli jeeps leapt into the open area, separating my house from the Martyrs Graveyard. Children ran in panic. Teargas grenades were lobbed in frenzy. Kites fell all around like wounded eagles. I too ran, in circles, without letting go of my kite.

It was not bravery. Far from it. I was frightened beyond comprehension. But it took me months to finally have a kite, and when I finally had one, and an amazingly beautiful one at that, I was not ready to let go. A jeep sped towards me, as my hand trembled. “You, jackass,” a soldier yield in a loudspeaker. “Let go of the kite.” And so I did. When I was asked why I was crying, many hours later, I told my brothers that my eyes were still irritated from the tear gas. But that was a lie.

It was because of this bittersweet memory, perhaps, that the news reports of Gaza’s children aiming for the world record on the number of kites flown stimulatingly in the same place, captured my attention. John Ging, the director of operations for the UN Relief and Works Agency assured reporters that the 5,000 children who gathered by the beach in northern Gaza, on July 30, have indeed broken the record. The previous record was set in Germany in 2008, and if the new feat is verified by Guinness, Gaza’s kids will have taken the lead with “flying colors”.

UN officials in Gaza, media reporters and others saw the kite flying event as an expression of innocence in a time when Gaza lives its harshest periods yet: suffocating siege, massacres, and collective humiliation. But the message was, of course, neither about kites, nor about world records. It was about the children of Gaza, in fact, Gaza itself, that tiny, subjugated, yet ever resilient, defiant, proud and somehow still hopeful place.

As for me, I never knew of the whereabouts of my old kite when I so reluctantly let it go. I was comforted by the thought that it might have fallen into the detention center, but I was never sure. It was my first kite ever, and I never asked for another one despite my older brother’s repeated offers.

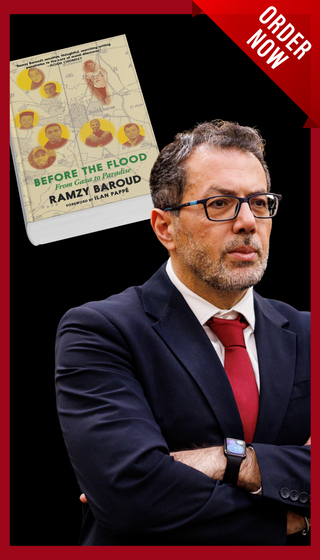

– Ramzy Baroud (www.ramzybaroud.net) is an author and editor of PalestineChronicle.com. His work has been published in many newspapers, journals and anthologies around the world. His latest book is, "The Second Palestinian Intifada: A Chronicle of a People’s Struggle" (Pluto Press, London), and his forthcoming book is, "My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story" (Pluto Press, London).

0 Comments