Lurking Dangers to the Arab Quest for Freedom and Reform

Image Credit: Illustration: Dana A. Shams/©Gulf News

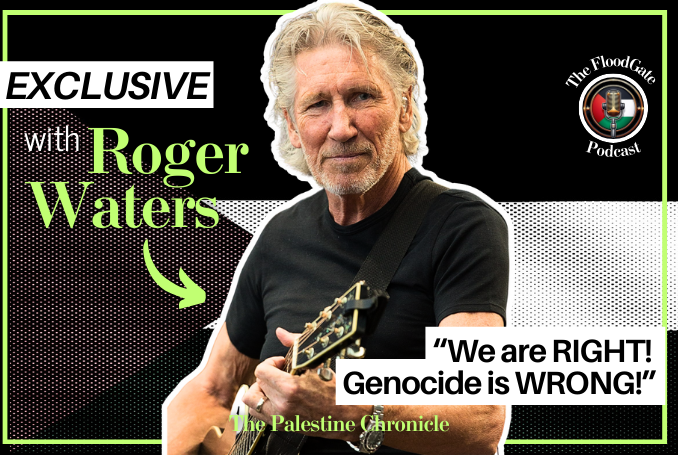

By Ramzy Baroud, Special to Gulf News

Arab revolutions are currently facing real dangers, which vacillate between lack of prioritisation, stagnation and foreign intervention.

In Egypt, there have been deliberate attempts to divide the objectives of the revolution into blurred ideological classifications. A chasm is already growing between ‘liberal’ and Islamic forces regarding the identity of the state. Endless debates have ensued regarding the best course of action pertaining to elections, the constitution and more.

The trial of former president Hosni Mubarak has been marketed as a major victory for the revolution. Undoubtedly this is a historic event with great psychological impact. Many in Egypt were suspicious that the military was trying to co-opt the revolution, and some believed that Mubarak was continuing to run the country from his Sharm Al Shaikh mansion. With the world having now seen Mubarak in prison garb, some of these rumours are being quelled.

Still, it must not be forgotten that Egypt’s problems are multi-faceted, running deep into the very fabric of its political and social structures. Its already threadbare economy was also further devastated by recent events.

Presenting Mubarak on a stretcher for ‘conspiring to kill protesters’, and then falling into the trap of disputes around political semantics will not resolve the country’s many problems.

The Yemeni people persist between clear objectives and unclear strategy. Yemen was already teetering on the brink of ‘failed state’ status before the February revolt. The opposition is clearly failing to unify the revolutionary efforts of the people. The aim has been to create a meaningful political platform capable of translating the just demands of millions into a clear roadmap.

This has no room for Ali Abdullah Saleh and his discredited government. A delay of nearly six months has allowed regional and international forces to impede the popular process aimed at democratic reforms. Frustrated by the ineptness of the opposition, and worried about the devious role played by outsiders, the ‘youth of the revolution’ moved to establish their own transitional political body.

This move seemed to create more confusion rather than actually address the challenge of political centrality. Saleh and his ruling party are feeling emboldened once again and are bargaining politically with a nearly-starved population. As for Libya, it has turned into a battlefield. Although the people’s original demands for democracy are as genuine as ever, linking the heart of the revolution to Nato’s central command has more than tainted the uprising.

It has also raised the spectre of western intervention in Libya. The billions of dollars spent to ‘liberate’ Libya will be recovered through political and economic leverages later on. This will prove very costly for any new Libyan government.

Three Principles

The Syrian revolution has been most inspiring. Despite the extremely violent behaviour of the army in its attempts to subdue the uprising, the people remain committed to three major principles: the rightful demands of their revolution, the non-violent nature of their efforts, and non-interventionism. That said, foreign intervention does not seek people’s permission; it seeks opportunities.

It is guided by a straightforward cost-benefit analysis. As for violence, even noble revolutions with noble demands have limits. How long will the Syrian people endure before resorting to arms, at least to defend themselves against the government’s thugs?

There are other Arab countries that are also experiencing their own upheavals. These are divided between betrayed revolutions (for example, Bahrain), revolutions in the making, and bashful reform movements (Jordan, Morocco, Algeria, and others).

True, each revolutionary experience remains unique. The socio-economic specificities of a wealthy Gulf country are different from those of a poverty-stricken country like Morocco. Still, Arab countries have much in common. Aside from shared histories, religions, language and a collective sense of belonging, they also share experiences of oppression, alienation, injustice and inequality.

The third UN Arab Development Report, published in 2005, surmised that in a modern Arab state, "the executive apparatus resembles a black hole which converts its surrounding social environment into a setting in which nothing moves and from which nothing escapes."

Things didn’t fare much better for Arab states in 2009, when the fifth volume in the series claimed: "While the state is expected to guarantee human security, it has been, in several Arab countries, a source of threat undermining both international charters and national constitutional provisions."

It is this shared fate that makes an Egyptian woman protest the violence carried out by the Syrian regime, and which drives a Tunisian man to celebrate the trial of Mubarak.

Coupled with a joint understanding of their history — which includes the struggle against colonialism and continued oppression in the neo-colonialist era — the Arab sense of solidarity is almost innate.

There is no question that in a post-revolutionary Arab world, a new collective sense of identity will emerge, this time without the manipulation of a single charismatic leader.

Revolution is a process, a progression of realisations borne out of experience. It seeks real and lasting change. It spans in its outreach from the realm of politics into the specificity of identity and self-perception. Because Arab revolutions are real, they also represent a real danger to foreign powers and their local alliances.

The self-seeking concoctions will use all their power to impede the process of change and reforms in the Arab world. This helps to explain the shedding of doubts on the authenticity of the youth movement in Egypt; the collective punishment of Yemenis; the brutalising of revolting masses in Syria.

Arab revolutionaries must be wary of all of these challenges. They must prepare for all grim possibilities. With unity being their greatest weapon, the revolutionaries need to remember that a victory in Egypt or Tunisia is an important step in the quest for freedom in Yemen, Syria — and everywhere else.

– Ramzy Baroud is an internationally-syndicated columnist and the editor of PalestineChronicle.com. His latest book is My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story.

0 Comments