Arab Springboard for Intervention? Two Years of Revolution and War

By Ramzy Baroud

Reform movements in the Arab world are indicative of the rise of new players in a political game historically reserved for the locals and their western benefactors.

On January 25, Egyptians commemorated the second anniversary of their revolution. Some spoke of historic achievements, others bemoaned lost opportunities and many more were just not sure what to say. The last two years, with all of their ups and downs, bloody encounters and electoral face-offs, can be dissected and rationally explained within an Egyptian context. However, once the Egyptian experience is framed within the larger analysis of the conveniently coined Arab Spring, logic goes awry.

Despite the fact that the Arab media is equally responsible for promoting an unqualified narrative of an Arab Spring or an Arab awakening, western media and governments were barely making passing references. By reducing Arab people — with their immeasurably complex social fabric, political realities, economic situations, religious and sectarian diversities etc — into one single unit of analysis, no sensible conclusion can possibly be obtained.

However, a two-year discourse has been carefully molded to achieve just that — summoning all sorts of misguided perceptions and equally misguided policies. Of course, misconceptions have defined the West’s tumultuous relations to the Middle East for many years. Western notions or policies in the Arab region have continuously hovered around orientalist fantasies, self-centered economic interests and political and military opportunism. These injudicious agendas have, over time, evolved into an unsettling elitist group-think that views Arab societies or Arabs through a racist, reductionist and self-seeking prism.

Expectedly, a complete discourse has morphed over the years to correspond to these ill-advised perceptions; a discourse that selectively tailors its reading of Arab-related matters in such a way as to only yield desired outcomes which leave little or no room for other inquiries, no matter how appropriate or relevant.

True, Arab revolutions, uprisings or at least the notable social upheavals registered in various Arab societies, have clearly inspired many groups and collectives to aspire for change, reforms, freedom and democracy. For western governments, such mass movements — once reduced to one single phenomenon — represented opportunities to be grabbed, weak spots to be exploited and even conflicts to be endlessly fed even at the expense of tens of thousands of innocent victims.

The so-called Arab Spring, although now far removed from its initial meanings and aspirations, has become a breeding ground for choosy narratives solely aimed at advancing political agendas which are deeply entrenched with regional and international involvement.

However, that is not how it all began. When a despairing Tunisian street vendor, Mohammad Bouazizi, set himself on fire on December 17, 2010, he had ignited more than a mere revolution in his country. His excruciating death had given birth to a notion that the psychological expanses between despair and hope, death and rebirth and between submissiveness and revolutions are ultimately connected. His act, regardless of what adjective one may use to describe it, was the very key that Tunisians used to unlock their ample reserve of collective power. The then president, Zine Al Abidine Bin Ali’s decision to step down on January 14, 2011, was in a sense a rational assessment on his part — if one is to consider the impossibility of confronting a nation that had in its grasp a true popular revolution.

However, when US Secretary of State Hilary Clinton made an appearance in front of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee last Wednesday, to comment on the violent death of the US Ambassador to Libya and three other Americans on September 11, last year, the Arab Spring for her meant something entirely different. For US policymakers, the spring now represents a security threat or an opportunity. “Benghazi didn’t happen in a vacuum,” Hillary said. “The Arab revolutions have scrambled power dynamics and shattered security forces across the region.” Indeed, Benghazi was supposed to be another success story of western military intervention, except it eventually backfired and thus Washington was bewildered over the unpredictable Arab weather patterns.

Tunisia might have been the harbinger of revolutions, but it was Egypt that first linked the Tunisian uprising to the upheavals that travelled throughout Arab nations. Some were quick to ascribe the phenomenon to all sorts of historical, ideological and even religious factors, thereby establishing links whenever convenient and overlooking others however aptly.

Not only do the roots and the expressions of these “revolutions” vastly differ, but the evolving of each experience is almost always unique to each Arab country. In the cases of Libya and Syria, foreign involvement (an all-out Nato strike in the case of Libya and a multifarious regional and international powerplay in Syria) has produced wholly different scenarios than the ones witnessed in Tunisia and Egypt, thus requiring an urgently different course of analysis.

Uprisings in some Arab countries and growing movements towards reforms in others are all indications of the rise of some Arab societies as new players in a political game that was historically reserved for local elites and their western benefactors. Apart from its numerous failures, the all-inclusive Arab Spring discourse delineates only one element of the current political landscape in some Arab countries. It largely ignores the counter-revolutionary forces exemplified in regional powers and western interventionists. In many ways, the latter two forces seem to have the upper hand in terms of their ability to manage, and at times, feed post-revolution chaos. Their combined political sway, financial power and military advantage make these forces the gatekeepers in engendering or dismissing popular movements altogether.

Yet, despite the repeated failures of the unitary Arab Spring discourse, many politicians, intellectuals and journalists continue to borrow from its very early logic. Books have already been written with reductionist titles, knitting linear stories, bridging the distance between Tunis and Sana’a into one sentence and one line of reasoning.

Reporting on the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland (Jan 23-26), where the Arab Spring was a primary focus, an AP report summed up the sweeping generalizations of western media and Davos groupthink mentality as such: “The uprisings that first began in Tunisia in December 2010 did bring down dictators in Tunisia, Yemen, Libya and Egypt. But now Islamists and liberals wrangle over power, with the former mostly on top, democracy is far from certain, and economies are crumbling.” Never mind that Libya’s revolution prevailed because of Nato’s destructive war and that Yemen’s revolutionary success was a political doctrine achieved outside the country, without the consent of the people and that Syria’s uprising was hijacked by numerous agendas, some sectarian and few are concerned with the future of the systematically destroyed country.

But reductionist discourses persist, despite their numerous limitations. Western media continues to lead the way in language manipulation. US media, in particular, remains oblivious to how the fallout of the Nato war in Libya had contributed to the conflict in Mali — which progressed from a military coup early last year into a civil war and as of present time an all-out French-led war against Islamist and other militant groups in northern parts of the country.

Mali is not an Arab country. Therefore, it does not fit into the carefully molded discourse. Algeria is, however. Thus, when militants took dozens of Algerian and foreign workers hostage in the Ain Amenas natural gas plant in retaliation of Algeria’s opening of its airspace to French warplanes in their war on Mali, some labored to link the violence in Algeria to the Arab Spring. “Taken together, the attack on the US Embassy in Benghazi, Libya, the Islamist attacks on Mali and now this Algerian offense, all point to north Africa as the geopolitical hotspot of 2013 — where the Arab Spring has morphed into the War On Terror,” wrote Christopher Helman, in Forbes, on January 18. The Arab Spring logic is constantly stretched in such ways to suit the preconceived understanding, interests or even designs of western powers.

To advance our understanding of what is transpiring in Arab and other countries in the region, we must let go of old definitions. A new reality is now taking hold and it is neither concerned with Bouazizi nor of the many millions of unemployed and disaffected Arabs.

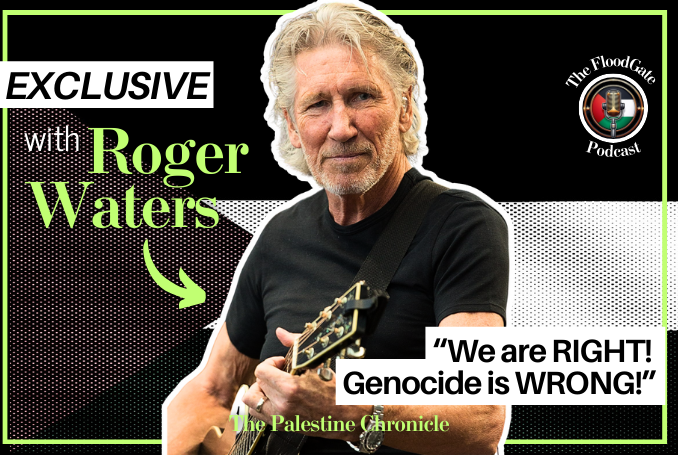

– Ramzy Baroud is an internationally-syndicated columnist and the editor of PalestineChronicle.com. His latest book is: My Father was A Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story (Pluto Press).

0 Comments