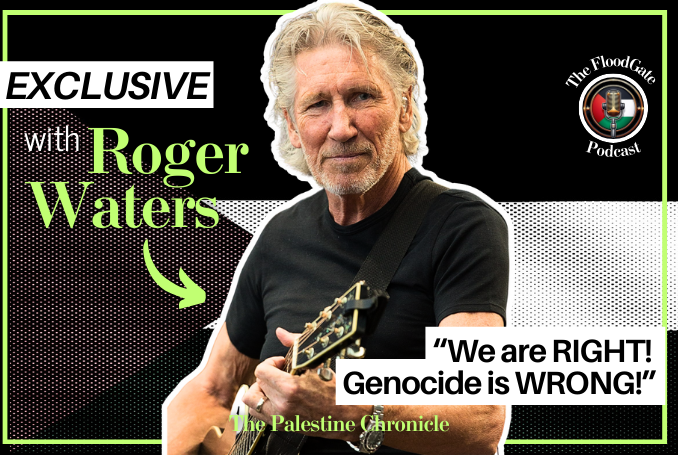

These Chains Will Be Broken. Palestinian Stories of Struggle and Defiance in Israeli Prisons – Book Review

Palestinian prisoner Khalida Jarrar (R) with her daughter Suha. (Photo: via Twitter)

By Ramona Wadi

(These Chains Will be Broken: Stories of Struggle and Defiance in Israeli Prisons, Clarity Press, Atlanta, 2019)

What the news reports eliminate, Ramzy Baroud’s new book, These Chains Will be Broken: Stories of Struggle and Defiance in Israeli Prisons, pushes to the fore. Palestinian prisoners, misrepresented through statistics, news reports, exploitation and glorification, tell slivers of their stories in this collection of first-hand narratives that stand as a testimony for both Palestinian resistance and resilience.

Khalida Jarrar is a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and the Palestine Legislative Council; she is also a freed prisoner, and sums up the book thus in her foreword:

“Each individual narrative is also a defining moment, a conflict between the will of the prison guard and all that he represents, and the will of the prisoners and what they represent as a collective, capable, when united, of overcoming incredible odds.”

Baroud’s introduction to the book departs from Antonio Gramsci’s definition of the organic intellectual and how this applies to Palestinian prisoners. In terms of narratives, consistency, and resistance, Palestinians embody this description, in particular when it comes to unity on several levels, including experiences, memory and anti-colonial struggle.

The collective that Jarrar speaks of is eliminated in external narratives of Palestinian prisoners and their families. Throughout this book, the reader is made aware of the differences between the summarised events for swift consumption, and the detail evoked by Palestinian prisoners and their family members.

Each narrative holds a sharp focus, an insight into one or a few particular memories, which contextualize the prison experience for both the narrator and the reader.

Some of the names in the book are familiar; others have been rendered anonymous due to the absence of media coverage regarding their case. Yet in each narrative, the sensationalism associated with certain Palestinian prisoners is abandoned; it is, indeed, non-existent. Herein lies the first difference between these narratives and the ones churned out by occasional media frenzies.

The individual stories are linked together through anti-colonial struggle, history, and memory. Not one single story is determined more valuable than the others on account of hunger strikes, for example, which is the media’s preferred story and one which harms the collective struggle of all Palestinian prisoners due to selective focus.

Instead, these brief narratives by prisoners and relatives expose an array of brutal violations endured by Palestinians in Israeli jails, as well as the intentional hatred and cruelty meted out by Israeli soldiers and prison guards. We read about one prisoner, for example, whose hands were scalded by a guard after she asked for tea.

Another prisoner was forced to watch a cat and her kittens get poisoned to death; that was the jailers’ punishment for seeking to bond with a living creature while in solitary confinement. In another case, ice packs were provided to prolong necessary medical attention for a broken ankle.

The institutionalized violence, in particular, the psychological aspect, is evoked in the narrative of a mother who, in her old age, was abruptly denied further visitation rights to her son, without reason.

Even prior to jailing, Israeli malevolence knows no limits. One Israeli police officer left a woman burning inside her car in order to claim that she had attempted to blow up the vehicle at a checkpoint.

With each narrative, the reader ponders the hidden face of colonization; the systematic and exceptional violence which has been normalized by silence about Israeli atrocities.

Key questions emerge: what do we understand about Palestine? How erroneously have we interpreted Palestinian prisoners, resistance and resilience? Why did we allow statistics to smother the humanity of Palestinian prisoners, their families and their stories?

One truth this book puts forth is an unconscious abandonment of the Palestinian story in favor of more manageable summaries. The brief introductions to each narrative in this book show the immensity of the Palestinian Nakba of 1948, as well as its repercussions on Palestinian families, decades later.

Loss of land and people motivated Palestinians to embrace the legitimacy of anti-colonial struggle only to be met with Israeli vengeance and generalized platitudes formed out of misunderstanding and misrepresentation.

Between memories of the Nakba, initiation into resistance and, for many prisoners, multiple life sentences, prison time is interpreted and experienced differently. For some Palestinian prisoners, the gap between incarceration and their loved ones becomes a focal point in isolation, which in turn brings out the comradeship between the prisoners themselves.

As one prisoner states after his mother passed away and funeral prayers were held for her within the prison, despite the guards’ objections,

“All the factions were there: Fatah, Hamas, the Socialists, and the Communists. We, Palestinians, are always united by hardship.”

Yet despite the abnormal conditions faced by Palestinian prisoners, their dignity is retained. As Israel’s prison system seeks to erode all of their rights, Palestinians have devised ways to counter the deprivation through unity and education.

Jarrar’s narrative is particularly powerful. Her quest to provide education for female Palestinian prisoners is summarized thus:

“I realized that there is a need to institutionalize the educational experience for female prisoners and not to tie it to me or any single person.”

For other detainees, knowledge became an important weapon to utilize against Israel’s colonial violence inside its jails. Contrary to uninformed perception, knowledge is not merely an action undertaken by prisoners to occupy their time. The strategic approach to knowledge is also part of the Palestinian anti-colonial struggle and learning is an integral component of the continuity of the resistance.

Richard Falk’s afterword to the book juxtaposes the Palestinian prisoners’ struggle against the international community’s adoption of the Israeli legal narrative, which, he insists, “attempts to marginalize international humanitarian law (IHL) as it applies to the Palestinian people.”

The isolation faced by Palestinian prisoners in terms of legality and solidarity are summed up in a succinct observation of the dynamics that govern the international community when it comes to human rights.

“It is a serious mistake to expect justice and lawfulness to be achieved by convincing governments and international institutions of Israel’s defiant attitudes towards international law,” writes Falk.

Baroud’s book is a testimony of perpetual wounds. Yet it is also a celebration of Palestinians, but only if this is done within the context of unadulterated Palestinian narratives. It is not our job to force interpretations of sentiments such as the isolation faced by prisoners, for example: “But time here keeps ticking slowly, and I just keep walking up and down, alone in my cell.”

It is our duty to listen, to create the spaces for such narratives to unfold as Palestinians wish them to. Anything less than that is an aberration.

– Ramona Wadi is an accomplished writer and an artist. Wadi is a staff writer for Middle East Monitor, where this article was originally published.

0 Comments