Beyond the Middle East: The Rohingya Genocide

At a Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh. (Photo: Zoriah.net)

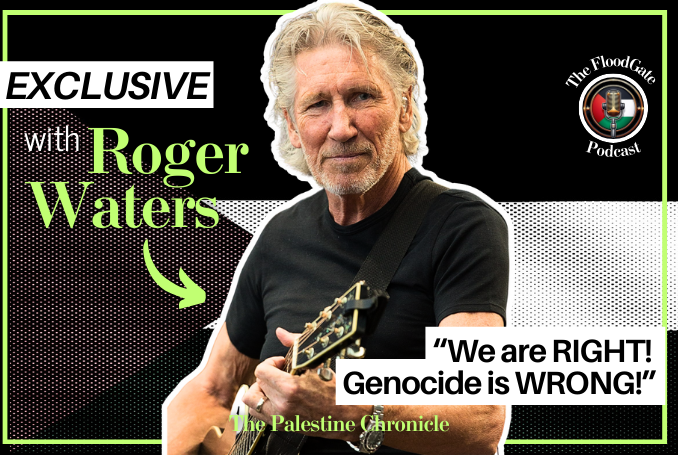

By Ramzy Baroud

“Nope, nope, nope,” was Australia’s Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s answer to the question whether his country will take in any of the nearly 8,000 Rohingya refugees stranded at sea.

Abbott’s logic is as pitiless as his decision to abandon the world’s most persecuted minority in their darkest hour. “Don’t think that getting on a leaky boat at the behest of a people smuggler is going to do you or your family any good,” he said.

But Abbott is hardly the main party in the ongoing suffering of Rohingyas, a Muslim ethnic group living in Myanmar, or Burma. The whole Southeast Asian region is culpable. They have ignored the plight of the Rohingya for years. While tens of thousands of Rohingya are being ethnically cleansed, having their villages torched, forced into concentration camps and some into slavery, Burma is being celebrated by various western and Asian powers as a success story of a military junta-turned democracy.

“After Myanmar moved from dictatorship toward democracy in 2011, newfound freedoms of expression gave voice to Buddhist extremists who spewed hatred against the religious minority and said Muslims were taking over the country,” reported the Associated Press from the Burmese capital, Yangon.

That “newfound freedom of expression” has cost hundreds of people their lives, thousands their properties, and “another 140,000 Rohingya were driven from their homes and are now living under apartheid-like conditions in crowded displacement camps”.

While one may accept that freedom of expression sometimes invites hate speech, the idea that Burma’s supposed democracy has resulted in the victimisation of the Rohingya is as far from the truth as it gets. Their endless suffering goes back decades and is considered one of the darkest chapters in Southeast Asia’s modern history. When they were denied citizenship in 1982 – despite the fact that it is believed they descended from Muslim traders who settled in Arakan and other Burmese regions over 1,000 years ago – their persecution became almost an official policy.

Even those who take to the sea to escape hardship in Burma find the coveted salvation hard to achieve. “In Myanmar, they are subjected to forced labour, have no land rights, and are heavily restricted. In Bangladesh many are also desperately poor, with no documents or job prospects,” reported the BBC.

And since many parties are interested in the promotion of the illusion of the rising Burmese democracy – a rare meeting point for the United States, China and ASEAN countries, all seeking economic exploits – few governments care about the Rohingya.

Despite recent grandstanding by Malaysia and Indonesia about the willingness to conditionally host the surviving Rohingya who have been stranded at sea for many days, the region as a whole has been “extremely unwelcoming,” according to Chris Lewa of the Rohingya activist group Arakan Project.

“Unlike European countries – who at least make an effort to stop North African migrants from drowning in the Mediterranean – Myanmar’s neighbours are reluctant to provide any assistance,” he said.

Sure, the ongoing genocide of the Rohingya may have helped expose false democracy idols like Noble Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi – who has been shamelessly silent, if not even complicit in the government racist and violent polices against the Rohingya – but what good will that do?

The stories of those who survive are as harrowing as those that die while floating at sea, with no food or water, or sometimes, even a clear destination. In a documentary aired late last year, Aljazeera reported on some of these stories.

“Muhibullah spent 17 days on a smuggler’s boat where he saw a man thrown overboard. On reaching Thai shores, he was bundled into a truck and delivered to a jungle camp packed with hundreds of refugees and armed men, where his nightmare intensified. Bound to shafts of bamboo, he says he was tortured for two months to extract a $2,000 ransom from his family.

“Despite the regular beatings, he felt worse for women who were dragged into the bush and raped. Some were sold into debt bondage, prostitution and forced marriage.”

Human rights groups report on such horror daily, but much of it fails to make it to media coverage simply because the plight of the Rohingya doesn’t constitute a “pressing matter”. Yes, human rights only matter when they are tied into an issue of significant political or economic weight.

Yet, somehow the Rohingyas seep into our news occasionally as they did in June 2012 and months later, when Rakhine Buddists went into violent rampages, burning villages and setting people ablaze under the watchful eye of the Burmese police. Then Burma was being elevated to a non-pariah state status, with the support and backing of the US and European countries.

It is not easy to sell Burma as a democracy while its people are hunted down like animals, forced into deplorable camps, trapped between the army and the sea where thousands have no other escape but “leaky boats” and the Andaman Sea. Abbott might want to do some research before blaming the Rohingyas for their own misery.

So far, the democracy gambit is working, and numerous companies are now setting offices in Yangon and preparing for massive profits. This is all while hundreds of thousands of innocent children, women and men are being caged like animals in their own country, stranded at sea, or held for ransom in some neighbouring jungle.

ASEAN countries must understand that good neighbourly relations cannot fully rely on trade, and that human rights violators must be held accountable and punished for their crimes.

No efforts should be spared to help fleeing Rohingyas, and real international pressure must be enforced so that Yangon abandons its infuriating arrogance. Even if we are to accept that Rohingyas are not a distinct minority – as the Burmese government argues – that doesn’t justify the unbearable persecution they have been enduring for years, and the occasional acts of ethnic cleaning and genocide. A minority or not, they are human, deserving of full protection under national and international law.

While one is not asking the US and its allies for war or sanctions, the least one should expect is that Burma must not be rewarded for its fraudulent democracy as it brutalises its minorities. Failure to do so should compel civil society organisations to stage boycott campaigns of companies that conduct business with the Burmese government.

As for Aung San Suu Kyi, her failure as a moral authority can neither be understood nor forgiven. One thing is sure, she doesn’t deserve her Noble Prize, for her current legacy is at complete odds with the spirit of that award.

– Ramzy Baroud – www.ramzybaroud.net – is an internationally-syndicated columnist, a media consultant, an author of several books and the founder of PalestineChronicle.com. He is currently completing his PhD studies at the University of Exeter. His latest book is My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story (Pluto Press, London).

0 Comments